Consumer culture is probably my favorite subject to study (yes, I even like it more than researching Art). So I’ll admit it: after watching the show Mr. Selfridge I figured I had to find a way to write about it and still make it fit on my series of Women in History. One of my favorite series of documentaries out there is Dr. Pamela Cox’s Shopgirls: the true story of life behind the counter, and I have watched it so many times I have literally lost count. So what better way to pay homage to it? I promise I tried my best to add on Dr. Cox’s research, which was not the easiest thing to do as hers is amazingly done and information about the history of shopgirls is not readily available. So! What am I rambling on about? Why is this oh so very interesting and important?

Shopping back in the day

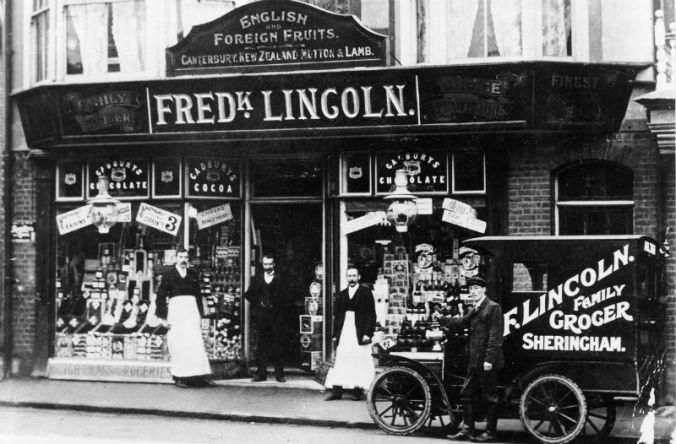

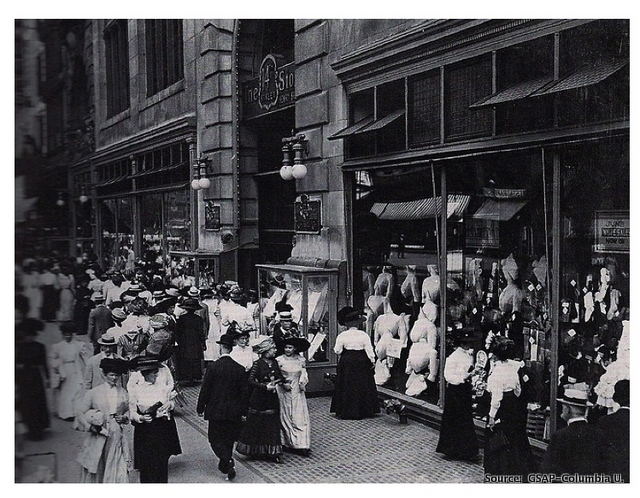

Shopping: admit it, we all love it. But going into a shop, picking something from the shelves, paying for it and being on our way was not how it was done not too long ago, believe it or not. Shops were usually family owned (specifically by the men of the family – although some widows could manage their husbands’ shops), and they hired young male apprentices who lived in the shop. Why only men? Well… to put it bluntly it was believed that women were too stupid to do the math, too weak to be on their feet all day long, and that they lacked the competitive drive to run a business. Yeah, never mind that women usually didn’t receive education (specially not maths), and that it was thought to be “unlady-like” to be anything other than cute and pleasant, and that you had to wear corsets, crinolines and long skirts all day long, BUT HEY! Let’s just hire men, shall we?

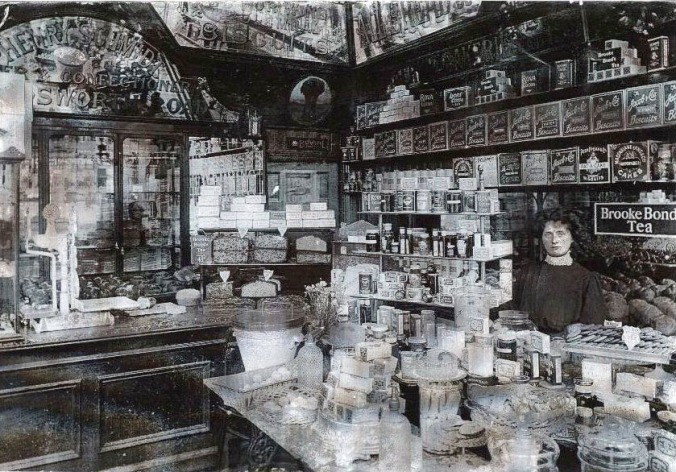

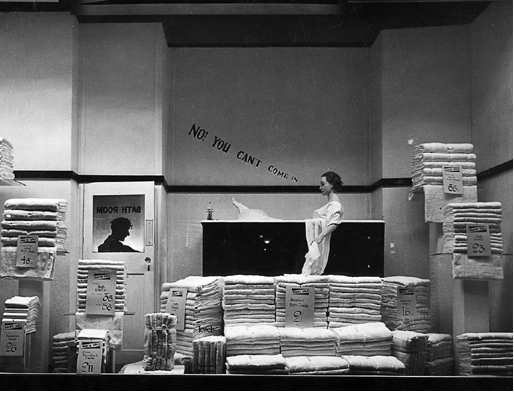

So, you come into a shop, entirely run by men (yes, even those selling trims and ribbons) and what could you expect to find? Well, for starters, goods did not have the price on them, so you had to ask… and haggle. The counters were high and every item was stored behind it. So if you wanted to see something you had to ask the shop keeper for it… and going into a shop and “just looking”? Good luck with that! You would get kicked out of the store for it. In fact, fancy shops had something called the “floorwalker” who would serve as a doorman and security guard. And if they noticed that you weren’t actually going to buy anything, they would ask you to leave not to keep wasting their time.

But! As industrialization kicked off cities started to grow and people began travelling around the world, and men in the working classes moved into new jobs in factories, which meant that there were more jobs available for women (other than service, agriculture and factories, which was the usual). In fact, in Britain there were more women than men, so with new jobs available single women on the working class could become, shock, self-supportive! And yet, a female shop assistant was paid half of her male counterpart’s salary. This wage gap comes from the principle that men were expected to support their entire family and women were expected to be kept by their husbands or just help make ends meet, at the most. And what about single mothers? Yeah, Victorians liked to ignore those as they were the incarnation of everything vicious and immoral.

Industrial transformation also meant that there was a new spending population: the middle class was finally settling in, and they wanted to show off their wealth through consumer goods. I’m not going into this (not on this post anyway), but with industrial production and the discovery of new materials like cellulose, an entire industry based on knock off products emerged. You could now buy accessories that looked like expensive ivory or tortoise shell but were actually made of plastic, and they were dirt-cheap! Imagine that!

The new Department Stores

The 19th century also saw the emergence of the consumer culture. Imagine living in a world where you could have every sorts of goods from around the world readily available! Ok, fine. We’re used to that by now. But back in the day you had to make dues with what was available to you, locally. But in came the Department stores: huge retailing palaces where you could find all sorts of items from anywhere you could imagine. Now there was no need for you to go door to door to find everything you were looking for, because now it was all under one roof. The world’s first department store was Harding, Howell & Co’s Grand Fashionable Magazine at 89 Pall Mall in St James’s, London (opened in 1796).

The department store was a safe place for Victorian women to both work and shop. Charles Jenner, founder of the Scottish Jenner’s department store, understood that women were key to his business. Dr. Cox worded it perfectly in her documentaries: he understood that “women should be at the center of his business, on both sides of the counter”. Middle-class women now had a safe place where they could spend their time of leisure, away from the company of men and unchaperoned. As shopping became more popular, society developed a dual (and hypocritical, if you ask me) view about women who did it: it was a woman’s duty to shop for her family (and even the men of the family) but she was criticized for wasting her time in the shops, and labeled as selfish and frivolous. Sounds familiar? Yeah, we still do that. Stop it. No, seriously, men like shopping just as much as women (even more in some cases), they actually spend more than women do, but it’s just that women have a different shopping experience than men and, most importantly, they’re buying for everyone else in the family. So knock it off.

So, part of the shopping experience was to have custom made clothing or partly-custom made clothing (that is, you would buy the different pieces separately and then have a seamstress put the garment together for you with your measurements – you could DIY if you were into that). In fact, fashion became a huge business by the mid-19th century as Queen Victoria and Empress Eugénie put the caged crinoline, and the enormous skirts that came with it, into fashion (seriously, the average skirt needed about 40 yards of fabric). And you don’t only needed huge dresses – you needed several of them as upper class women were expected to change at least once a day (usually for supper). There was a boom in the textile trade and everything related to it (dyes, needles, pins, ribbons, bleach, starch, etc.) and with better distribution systems shops could now offer a wider selection of goods brought from farther places, and they could also buy in bulk. And this meant that bigger retailers could reduce their prices much more than the traditional, smaller, specialist shops. Now, going to a store and paying for your goods in cash right then and there was not how business was ran – in fact, these traditional shops had accounts for their customers which were paid annually… which often sank them into bankruptcy. The emergent department stores now also dealt in cash, which meant they had a lot more buying power. You can imagine now how this became big business.

The emergence of the Shopgirl

SO! Onwards we go. The emergence of shopping required the equivalent of women shopkeepers. Why? Because it turns out that women preferred being assisted by women. Shopgirls were more attuned to the needs of the middle class women and were able to provide a better experience for them (and thus elevate their shopping fever – because if you’re having a good time you’re more likely to shop again). Also, retailing became the perfect job for lower middle class women. Remember what I was saying about there being more women than men? Well, that goes for all social classes. Now, a rich woman had little to worry about if she was single, as her own family could support her. And working-class women, as happened with lower classes since the dawn of time, worked as soon as they could – so when they reached an age where it was clear they were not going to marry, at least they had training and experience. But the lower-middle class woman was raised to be a wife and a mother, and if she didn’t marry she was left unskilled and with no income, and with no jobs prospect. So the Women of Langham Place set up an organization to provide the basic education for women and, yes, that included skills they could use for shop keeping. Hoorrah!

‘A Portable Shop Seat’, a suggestion to help with the “standing evil” which caused maladies to shopgirls. Published on The Girl’s Own Paper, 1880.

But shop-keeping, although not as strenuous as factory jobs or farming, was very hard work. The hours were extremely long (back in the day there were no regulations as to how many hours someone was required to work, so they could work upwards to 100 hours a week), and they had to be on their feet all day long and would often go all day without eating. In addition to this, there was the living-in system: inheriting that old-age custom of having apprentices living in with the shop owners, shop assistants had to live either above the shop or nearby… and the expenses for living-in were taken out of their salaries (which was the perfect way to keep wages low). They even had fines for misconduct, which reduced their salaries even more (and that included fines for menial things such as having fresh flowers in their rooms). This meant that shopgirls (who were paid half as their male counterparts, don’t forget that), often had to turn to prostitution to make ends meet. Some reformers tried, but these conditions didn’t change until the 20th century (we’ll get there, if you’re still with me).

Here comes Selfridge’s

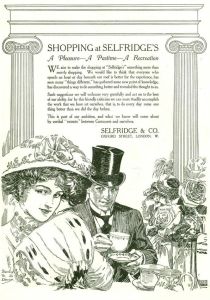

Opened in 1909 in London by Harry Gordon Selfridge, this department store would mark a before and after in the history of consumer culture. Harry was an American and had previously worked at Marshall Field’s where they pioneered in the policy of browsing. That’s right: you can thank him for now being able to say “no, I’m just looking” when you go into a shop and not being kicked out in the spot (he never hired floorwalkers). They also introduced the bargain basement, which was self-service at a time where customers had everything delivered to their house. He also brought the concept of providing customers with experiences and services not just goods: they had a restaurant, a reading room, a nursery for babies and, most importantly, A LADIES RESTROOM. Wait, what? Back in the day if you were a lady and wanted to go out shopping and maybe have a refreshment, you had to hold it in and go all the way back home if you needed to go to the toilet. Something as simple as that, and they were the first to think “well, if we want our customers to stay longer maybe we should give them a place to relieve themselves”. For him, shopping was also meant to be a pleasurable entertainment and so he focused on having well-informed, trained sales assistants who clearly loved where they worked.

H. G. Selfridge was very progressive. He believed in the power of advertisement and the media: just spread the word to get customers through the door, and once inside we will give them comfort, courteous service and entertainment as an enticement to buy. In fact, he invested more money on advertisement than any other retailer of his era. And part of his discourse was advertising the novelty of his shop, like having electricity (in fact, he was the first to leave his windows light at night, which was the birth of “window shopping” as we know it), the telephone, the facilities I mentioned before (as well as hair salons, barbershops, post office, etc.), and even introducing in-store art exhibits and cookery demonstrations. He was also pioneer in the way he advertised: he wasn’t pushy about buying, but rather, he talked about the philosophy of shopping, inviting the customers to sightsee, and reassured the quality, comfort and convenience of his services, as well the fair prices and the fun the customers could have on his shop. For the opening he launched a campaign with 38 illustrated advertisements, including a quite controversial one with a couple dining in his restaurant. Scandalous.

You know, when you go into a department store and the first thing you see is the perfume and cosmetics counters? Well, first one to do that was Selfridge’s. Back in Victorian times, the ideal of female beauty was very natural and clean, and make up (or at least obvious make up) was seen as very unlady-like so cosmetics were sold very discretely (after all, you weren’t really supposed to be wearing any). But with advances in technology not only cosmetics and perfume became more diverse, but they also became a lot more affordable with the dawn of synthetic chemicals. When Harry visited Paris in 1910 and saw that cosmetics and perfumes were openly on sale, he decided not only to expand Selfridge’s beauty department, but place it front and center – which was quite the shock to, well, everyone who hadn’t gone to Paris! Speaking of cosmetics and perfumes and shopping experience, Harry also believed that shopping should be “visual and tactile”, so he put central displays in the aisles with the merchandise which customers could touch, and he also lowered the counters to a “customer-friendly” level. In fact, he believed so much in this that Selfridge’s pioneered in the art of window dressing, introducing amazing, narrative displays that enticed the customers to look (and not just a pile of stuff, like it was customary at the time).

Selfridge’s was also detrimental to working women, as they employed 2,000 shopgirls and lift-assistants, with wages slightly higher than elsewhere. He also parted from the live-in system and banished the concept of pay-bans. However, it must be said, none of his female employees reached executive levels. In his own words, he wanted to “make their life as happy as possible. Feed and pay them well. Make them contented. To grind the life and soul out of a miserable white slave is sheer and bad business policy”.

Shopgirls and the fight for rights

Now, I hope you’re still with me, because here comes THE PUNKNESS. Yes, Harry Selfridge also supported the Suffragettes, and advertised in Votes for Women magazine, promoting merchandise such as ribbons and accessories in their colors – so much so that in the famous protest of 1912, Suffragettes broke all the shop windows on Oxford Street but spared Selfridge’s. This gives me a smooth transition to talk about them, so shall we?

Embed from Getty ImagesFirst we have Margaret Bondfield who was a shopgirl at the age of 21. While working as a shopgirl in London, she realized the grim realities of the job: long hours, low pay, and the living-in system – basically, shops owned their female employees. So in 1891 (this is way before Selfridge’s) she joined the National Union of Shop Assistants to expose the injustices faced by shopworkers as an undercover reporter. She wrote a series about life in the shop, describing the conditions they had to live and work in, and how easily you could lose your job for breaking the rules. Although recruiting workers for Unions was risky (even more so for shopgirls), her articles were the first spark in a series of changes. She also was supportive of universal voting rights, and not only votes for property owner (a.k.a.: upper class) women, which was the suffragettes’ cause. Plus, she eventually became the first female cabinet minister in the UK!

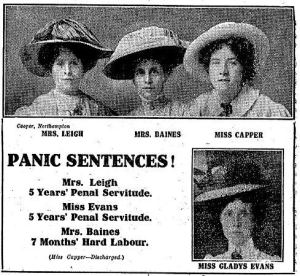

Then we have Gladys Evans, who actually worked at Selfridge’s at 17, and recruited fellow shopkeepers into the Union. She was such a militant suffragette that she is most famous for traveling all the way to Dublin in 1912 and setting fire to the (empty) theater where Prime Minister Asquith was scheduled to give a speech the following day (he was famous for haaaating Suffragettes’ guts). She was arrested, given a five-year sentence (which was very harsh, given the circumstances) and she went on a hunger strike and was force-fed for 58 days. Her fellow employees at Selfridge’s even wrote letters asking for her freedom. PUNK ROCK!

Then we have Gladys Evans, who actually worked at Selfridge’s at 17, and recruited fellow shopkeepers into the Union. She was such a militant suffragette that she is most famous for traveling all the way to Dublin in 1912 and setting fire to the (empty) theater where Prime Minister Asquith was scheduled to give a speech the following day (he was famous for haaaating Suffragettes’ guts). She was arrested, given a five-year sentence (which was very harsh, given the circumstances) and she went on a hunger strike and was force-fed for 58 days. Her fellow employees at Selfridge’s even wrote letters asking for her freedom. PUNK ROCK!

When the war came, shops across the country saw a shortfall in staff, which was made up by recruiting women: over half a million of them fled the servants’ quarters and sweatshops to work “man jobs”, including bus and ambulance driving, munition factories and even stoking the boilers. At Harrods 70% of the men had gone to war, so now they had women drivers and stock staff, and many other positions! In fact, women’s uniforms also became more utilitarian, and “[Harry G. Selfridge] also knew that his newly uniformed waitresses – now wearing trousers, could take ‘nine steps more per minute to get to the kitchen than they could in a skirt'”, noted in his diary in the 1920s. But more importantly all of this meant that women now had better wages and more spending power – even maids could now afford to go shopping as their wages doubled!

Embed from Getty ImagesWhen the war ended, men got their jobs back, but the perception about working women had changed fundamentally. Now, no one could say that women couldn’t do men’s jobs, because they had just proved they could! More importantly, they now had new skills and were better prepared. In fact, women returning to their old jobs were able to demand better conditions by going on strike, which set the wheels in motion to what we now know as the 40-hour working week.

This is the fifth article on my series about Women in History. You can read the last one about Ada Lovelace here. Tell me who you think I should write about next!

Pingback: Lili Elbe and Gerda Gottielb: defining gender through artistic representation | Laura Vianello